Certificate of Birth and Baptism.

Untitled (Gathering Mushrooms), 1972–1982, paint on cardboard, courtesy of the Monroe Family Collection.

George Voronovsky was born in Klepaly in 1903, a small village in Eastern Ukraine in what was then under the centuries-old monarchy that extended from the Pacific Ocean to the Black Sea known as the Russian Empire. Voronovsky belonged to a middle-class family—his father was a lawyer—and pursued music as a young adult, despite an early interest in visual art. He spoke fondly of his youth, and his colorful paintings, many of which were based on his experiences, transform these halcyon days spent in forests, fields, and city streets into evocative memoryscapes.

Demonstration in Kyiv for an independent Ukraine, Summer 1917.

With the onset of the Russian Revolution in 1917, which replaced Czarist imperial rule with Soviet Socialism, attempts were made to form an independent and self-governed Ukrainian nation, an effort that ultimately failed. By 1921, most Ukrainians were living under the Soviet Union. During this period, Voronovsky’s father died.

Voronovsky and family, ca. 1930s.

Untitled (Kyiv), 1978–1982, acrylic on canvas, courtesy of the Monroe Family Collection.

USSR internal passport, ca. 1941.

In 1932–1933, the people of Ukraine were subjected to genocide in the form of a famine engineered by a Soviet regime intent on eradicating nationalist resistance, resulting in the death of millions of Ukrainians. It is not clear how this impacted Voronovsky and his family, who were by that time living in Kyiv. After marrying Johanna Adamec there in 1933, Voronovsky became the father to two children, Oleksandr and Yarmila. Though he had studied to become a musician, he appears to have been working as a mapmaker during this period. By this time, Kyiv was a large metropolis, but in an era of political and cultural Russification, Ukrainian history was systematically erased, and the city’s distinctive Baroque churches were razed to the ground to make way for Stalinist architecture. The characteristic onion domes of the Ukrainian Baroque style abound in Voronovsky’s work, a record and memory of a bygone era.

A German sentry overlooking the Pechersk Lavra Monastery and Dnieper River in Kyiv, Ukraine, September 1941.

In 1941, Nazi forces invaded Ukraine as part of Hitler’s goal to subdue the USSR, code named Operation Barbarossa, and took Kyiv. Both the advancing German army and the retreating Soviet one were responsible for destroying much of the city.

Nazi camp transfer card, 1944.

When the Nazis took control of Kyiv in 1941, many Ukrainians who were not Jewish were forcibly relocated to resettlement camps like Gneisenau, where Voronovsky and his family were detained. A signed and stamped certificate from 1944, which Voronovsky kept until his death, records his transfer by forced march from the resettlement camp in Soldau (modern-day Działdowo in Poland) to Prague, about four hundred miles away. His wife and children were also transferred to Prague, but they were soon separated when Voronovsky was sent to a forced labor camp in Germany. Those who knew Voronovsky say he did not speak much about this troubled period in his life, although he did share that he took the heroic and subversive act of sabotaging machine guns destined for the German army while he was a work-group leader in the camps.

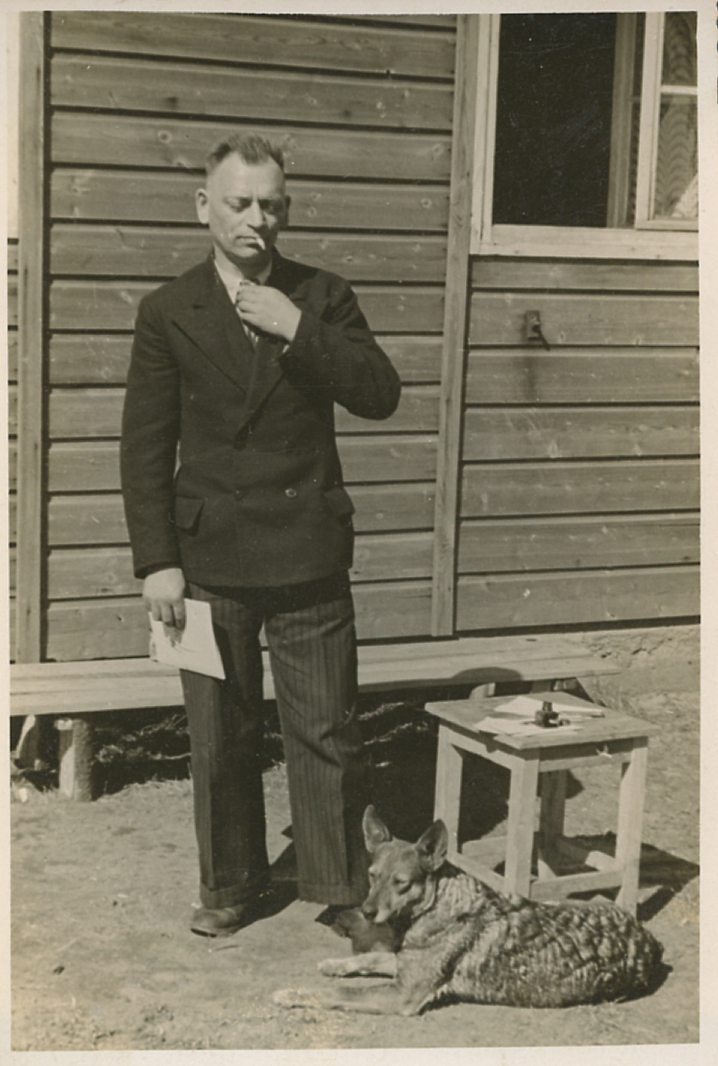

Voronovsky with dog, ca. 1948.

Voronovsky beside bushes, 1948.

Voronovsky playing accordion, ca. 1948.

After the end of the war in 1945, those who had been uprooted by the conflict—so-called Displaced Persons—were either voluntarily or forcefully repatriated to their countries of origin. For many Ukrainians, however, the destruction already inflicted on their home regions by the Nazis and the retaliatory politics of the Soviet regime—who regarded many forced laborers not as victims but as traitors—made a homecoming either untenable or undesirable. Rather than return to Soviet-controlled Ukraine, Voronovsky decided to remain in Displaced Persons camps, ad hoc communities of refugees organized by Western governments while they sought to resolve the humanitarian crisis. Many of the camps included a majority Ukrainian population; the camp where Voronovsky spent time, Camp Lysenko, was named for a Ukrainian composer.

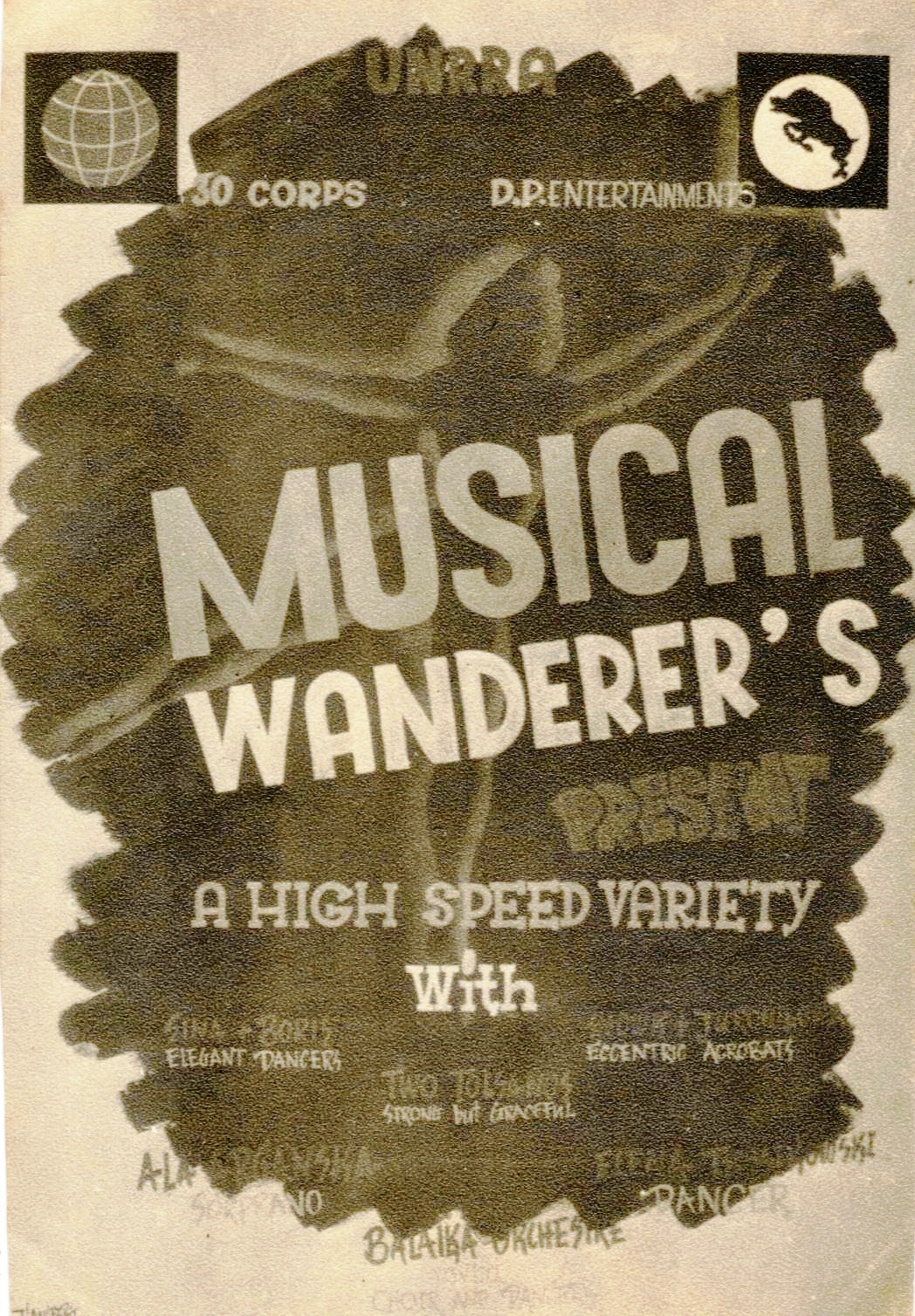

The Musical Wanderers, ca. 1945–1951.

Untitled (Dancers and Cheerleaders I), 1978–1982, paint on canvas, courtesy of the Monroe Family Collection.

Promotional poster for Musical Wanderers, ca. 1945–1951, collection of Phillip Shovk.

During this period, Voronovsky played with the Musical Wanderers, a Ukrainian folk music group that toured the Displaced Persons camps throughout the 1940s. The Displaced Persons camps were rich with cultural and political life, and groups like these would have contributed to a sense of cultural belonging among Ukrainians who had long lived under foreign powers. In a photo of the group, Voronovsky can be seen playing the banjo-mandolin, seated above the large “SND” placard. His many paintings of dance performances may hark back to the troupes he accompanied and saw perform during his time touring these camps.

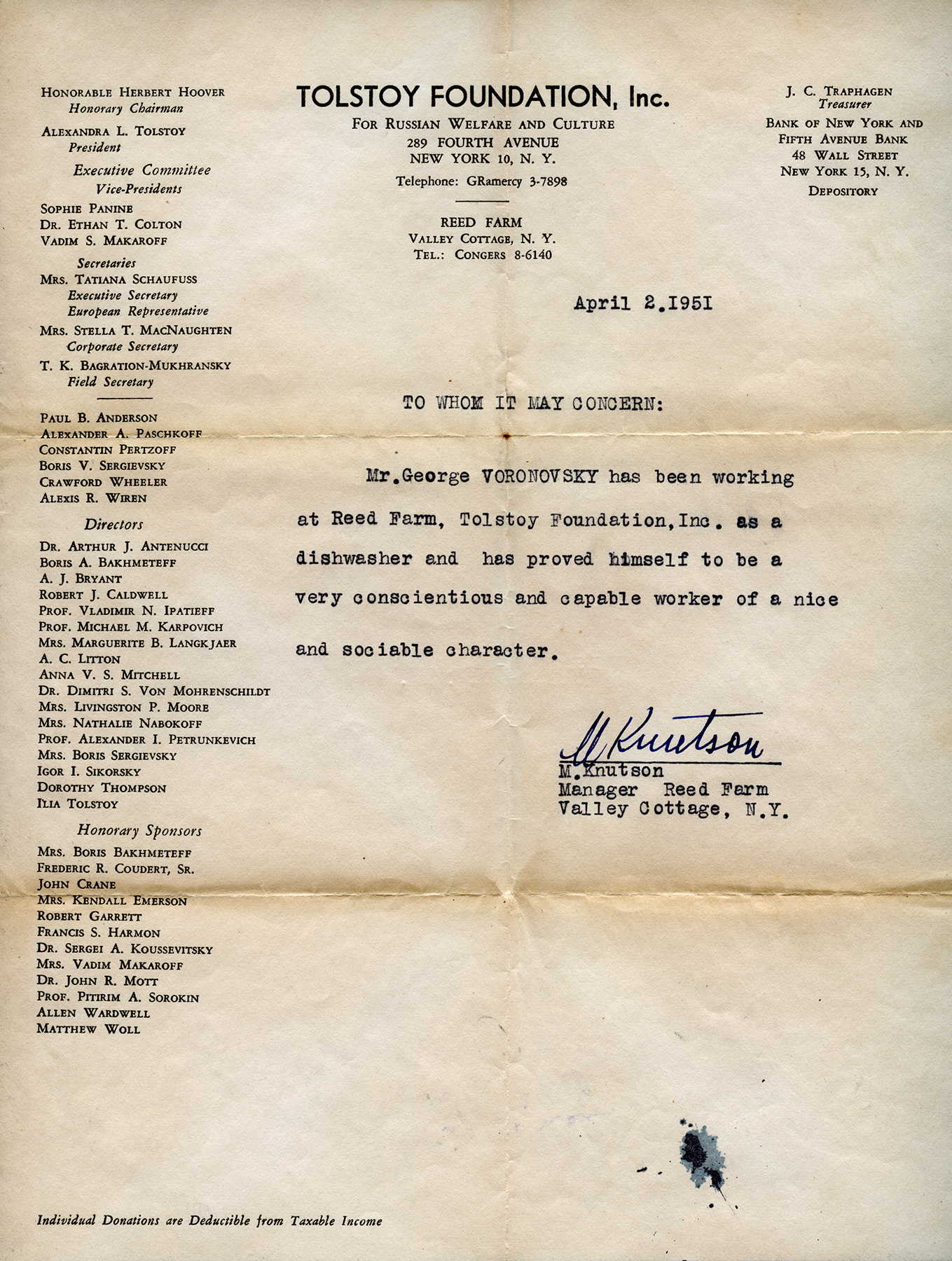

Reference letter for Voronovsky from Tolstoy Foundation, 1951.

After the passage in the United States of the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, which allowed thousands of Europeans to bypass previous immigration quotas, Voronovsky secured the support of the Church World Service and the Tolstoy Foundation, a nonprofit established by Alexandra Tolstoy—daughter of famed Russian author Leo Tolstoy—and headquartered in Valley Cottage, New York. Voronovsky arrived at Ellis Island on January 20, 1951, and was employed at the Foundation for a short time as a dishwasher.

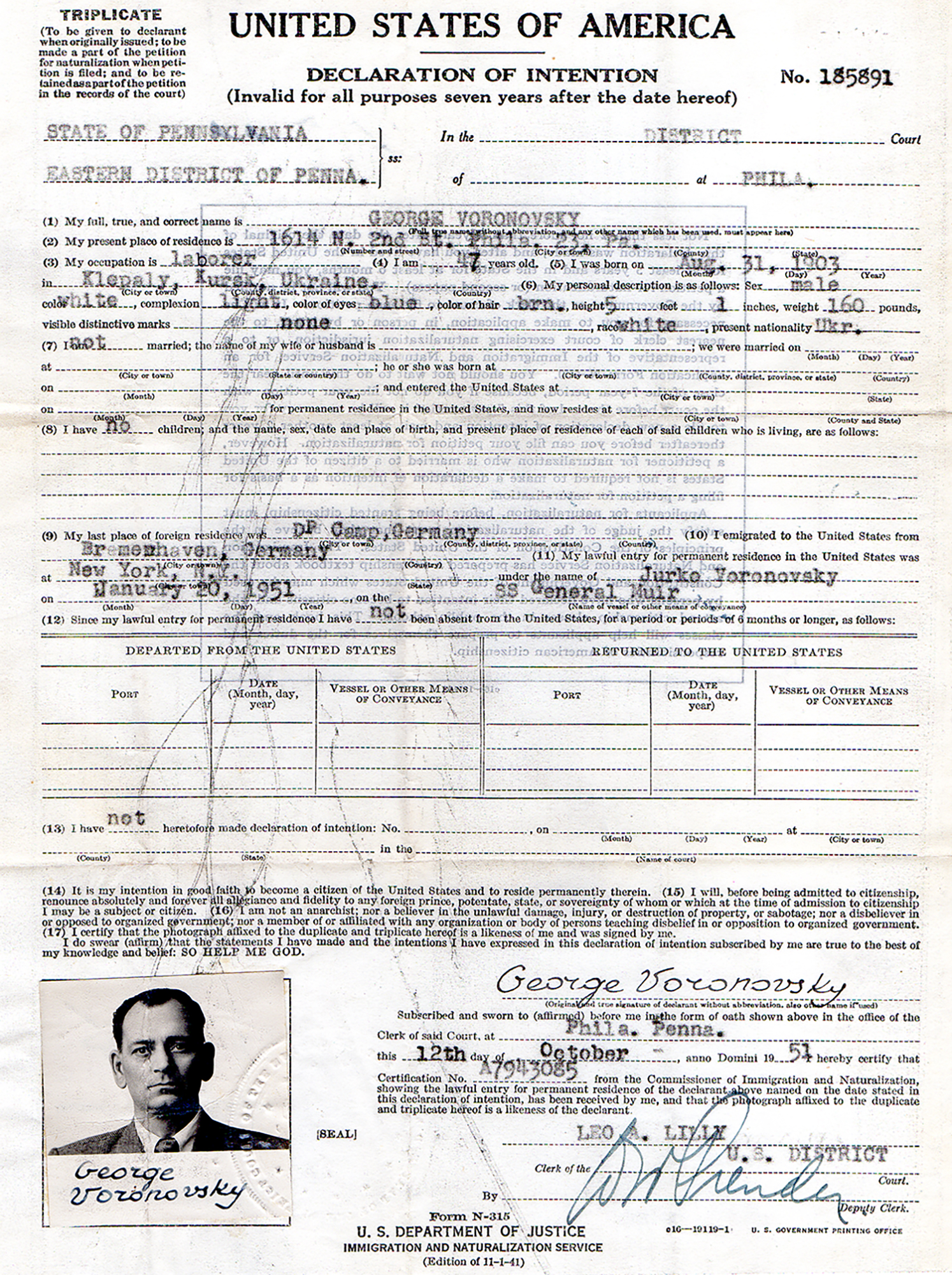

Voronovsky’s Declaration of Intention, 1951.

By late 1951, Voronovsky had moved to Philadelphia, already home to one of America’s largest Ukrainian communities and which grew significantly with a “Third Wave” of immigrants following World War II. In October, Voronovsky submitted his Declaration of Intention, the first step for immigrants hoping to become naturalized and eventually acquire citizenship.

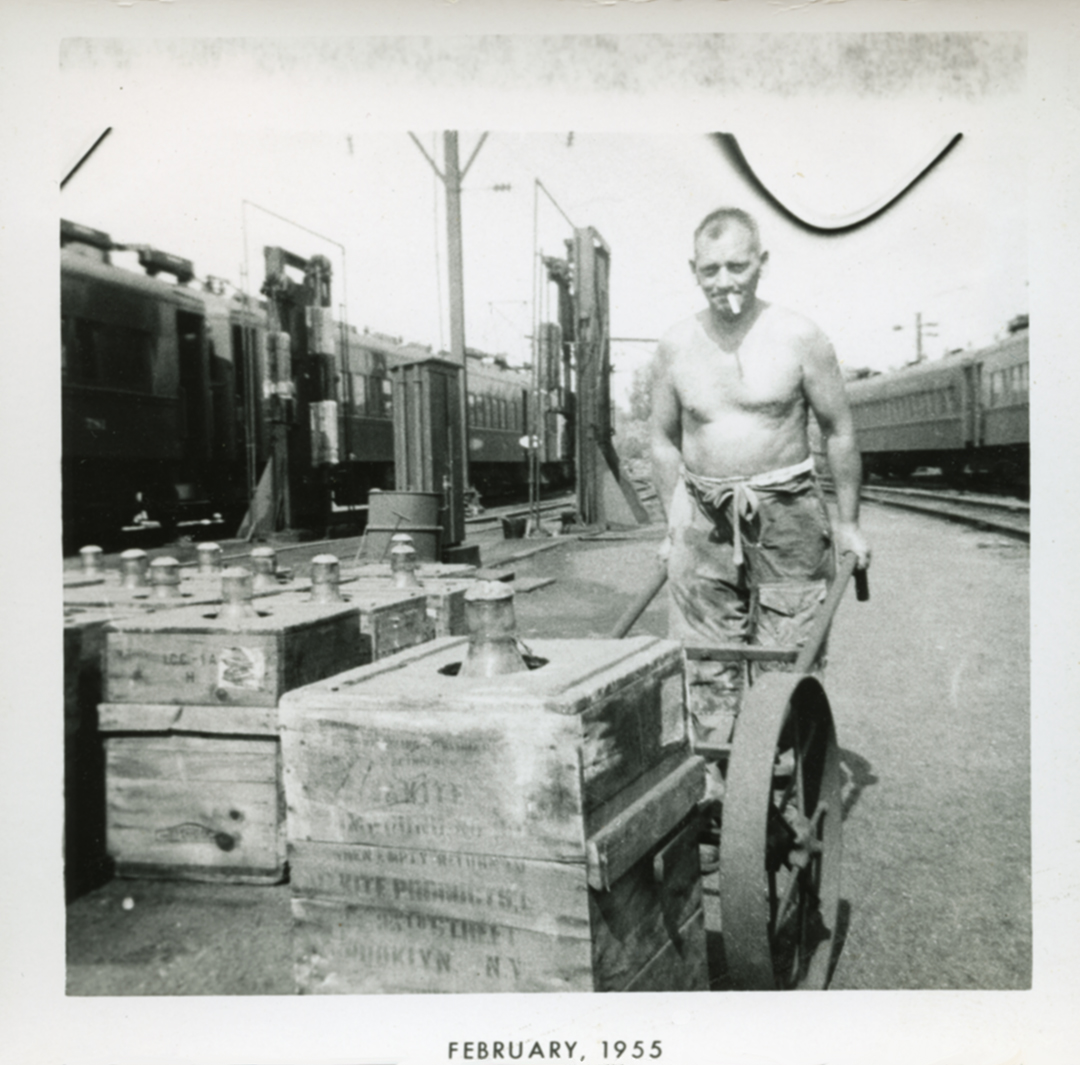

Voronovsky in front of rail car, 1954.

Voronovsky in train yard, 1955.

Voronovsky playing the accordion, 1955.

In Philadelphia, Voronovsky worked in the railroad industry executing numerous jobs, including acting as a train car cleaner and upholsterer. He settled in the predominantly Ukrainian neighborhoods northeast of downtown—where there is still a considerable Ukrainian presence—spending time with people who would have spoken his language and shared his love of music.

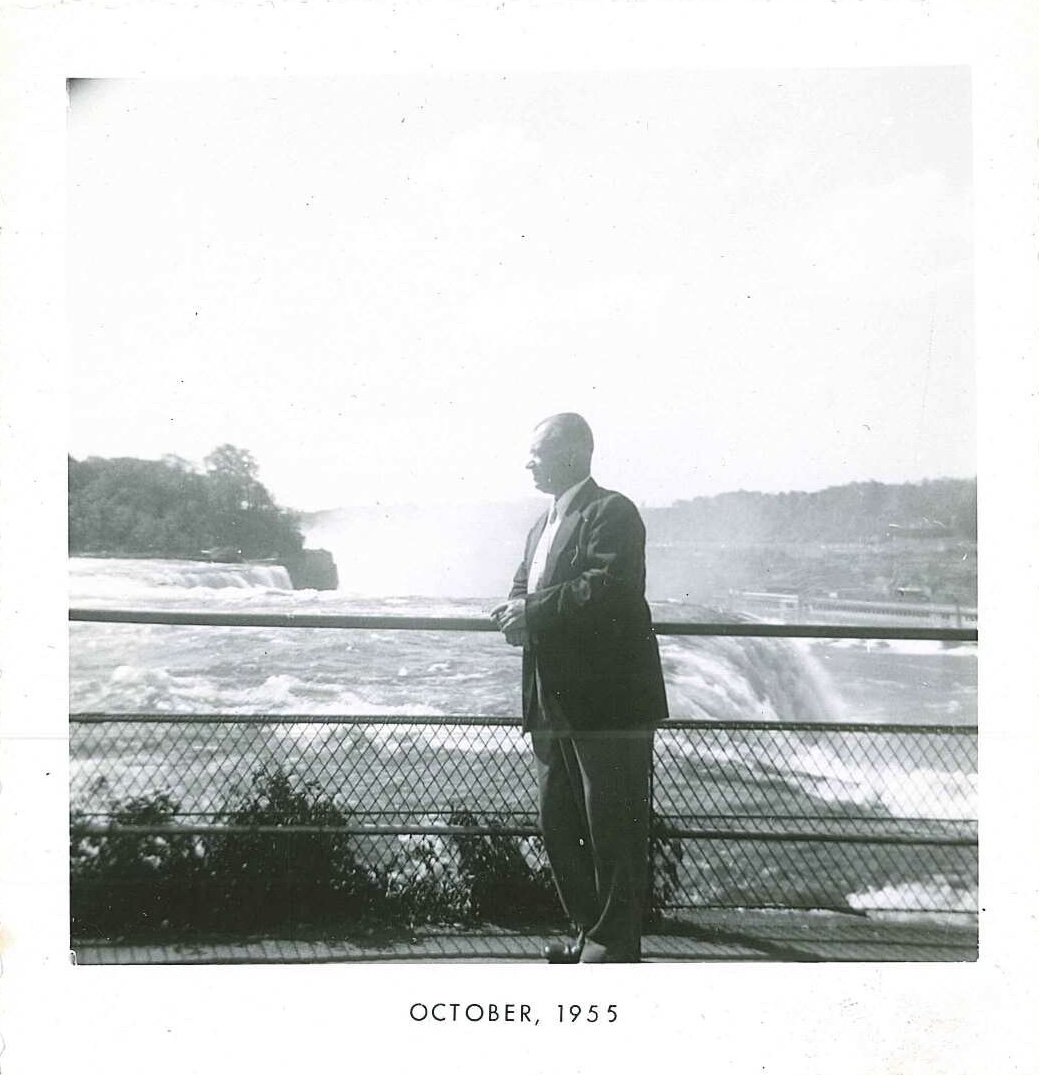

Voronovsky at Niagara Falls, 1955.

Voronovsky in field, 1956.

Voronovsky in Miami Beach, 1958.

Voronovsky was soon traveling across the country, taking the train or bus to destinations as far apart as Niagara Falls and Miami Beach. Friends of his from his time in Philadelphia remember spending time with him in Florida, a preferred destination for many Eastern European immigrants after World War II.

Voronovsky’s nude female wooden sculptures, 1960.

Untitled (Diving Nude Woman), ca. 1950s–1982, paint on wood and plastic, courtesy of the Monroe Family Collection.

In Philadelphia, Voronovsky filled his home with photographs, decorations, and some of his earliest surviving work—wood carvings of nude women in poses that suggest topless bathing or athletics. In service of the city’s large Ukrainian population, community organizations and church groups promoted Ukrainian folk music, dance, theater, literature, and visual art, assembling exhibitions that featured local artists. Voronovsky may have also engaged with museums like the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Mercer Museum, which had well-established collections and exhibitions on American folk art by this time. With their upright poses and simple bases, his sculptures resonate with forms that became central to the folk art canon that emerged in the twentieth century, such as weathervanes, whirligigs, and shop figures.

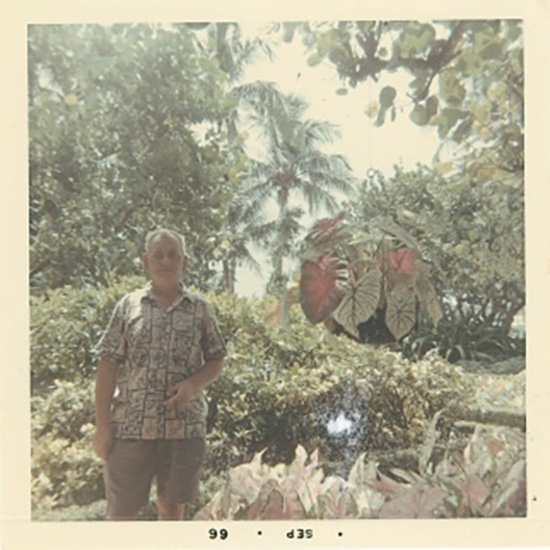

Voronovsky likely on a visit to the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Miami, 1966.

Voronovsky continued to travel throughout the 1960s, benefiting from some extra time off from his work in the railroads. Friends remember that one of his favorite places to visit was Miami’s Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. At some point in this period, he suffered a workplace injury to his leg, ultimately leading him to consider retirement and a permanent move to Florida.

Postcard of Colony Hotel, undated.

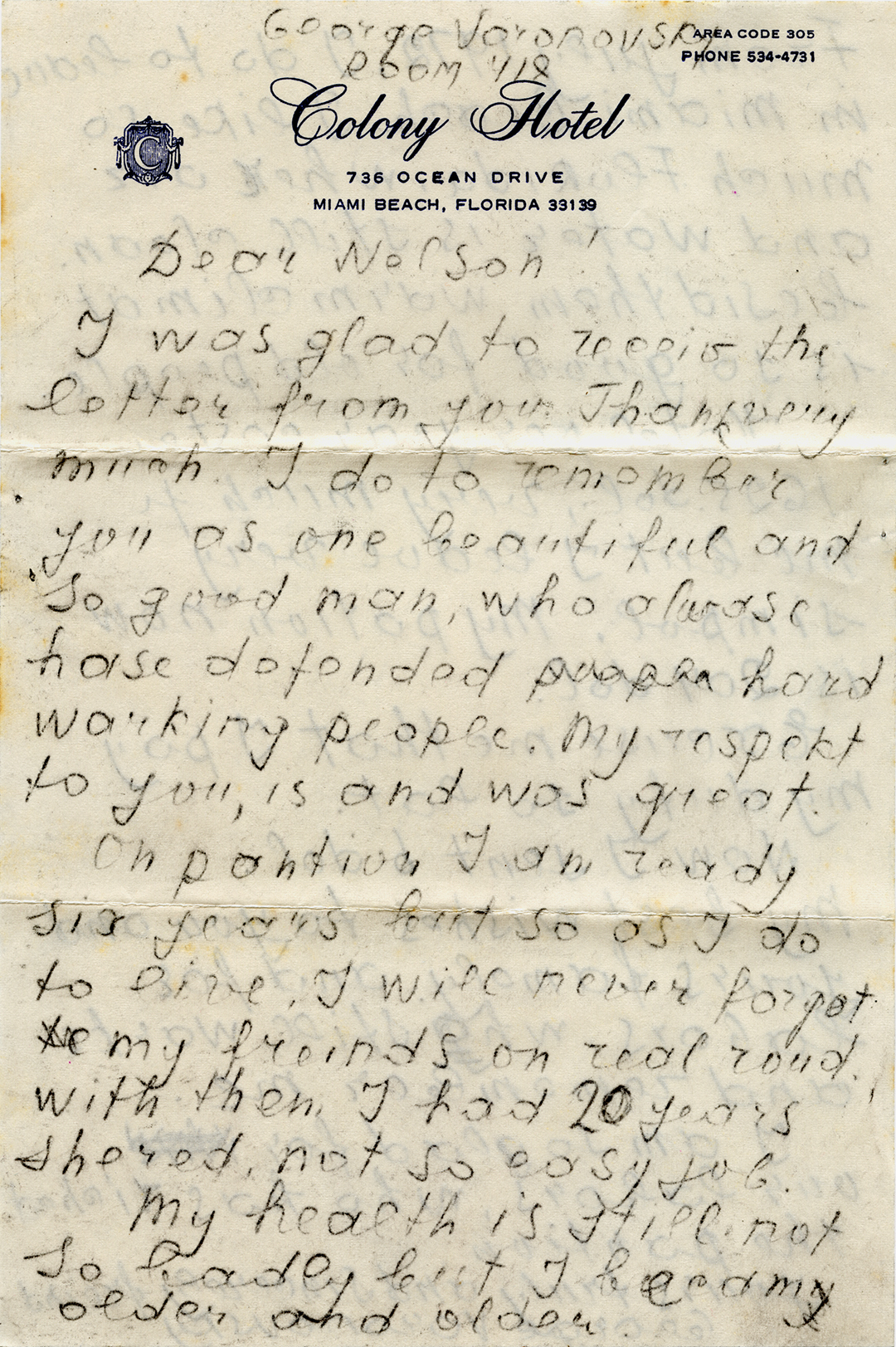

Letter from Voronovsky on Colony Hotel stationary, ca. 1978.

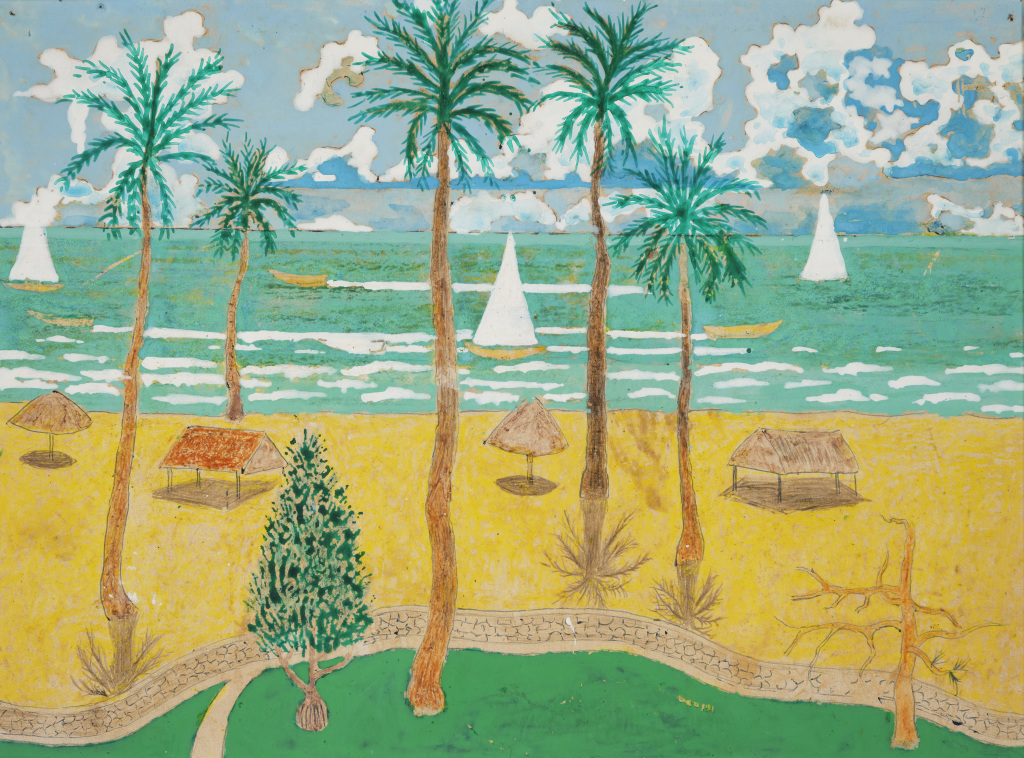

Untitled (Lummus Park, Miami Beach), 1972–1982, paint on cardboard, courtesy of the Monroe Family Collection.

By 1972, Voronovsky had moved permanently to the Colony Hotel on Ocean Drive in Miami Beach just across the street from Lummus Park, a green space on the south end of the island separated from the beach by a distinctive coral rock wall. The South Beach neighborhood where he settled was home to a large and aging Eastern European population. By the 1970s, the glamor of the 1950s and 1960s had faded and was yet to be revamped by the hot pink of the Miami Vice era. In this in-between period in the city’s development, Voronovsky spent time soaking his injured leg at the beach and frequenting the businesses that catered to his demographic, such as Colony Theatre on Lincoln Road—unrelated to the Colony Hotel where he lived—which showed films in Russian.

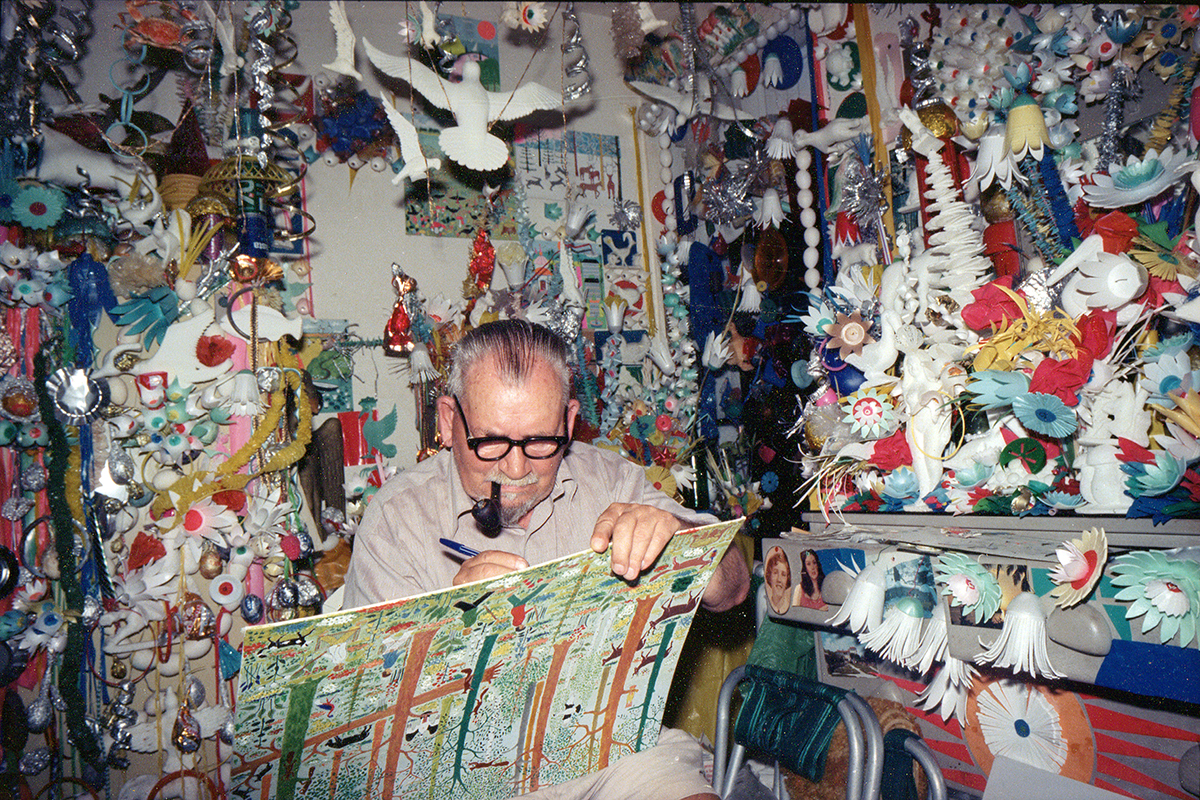

Portrait of Voronovsky, 1978–1982, by Gary Monroe (American, born 1951).

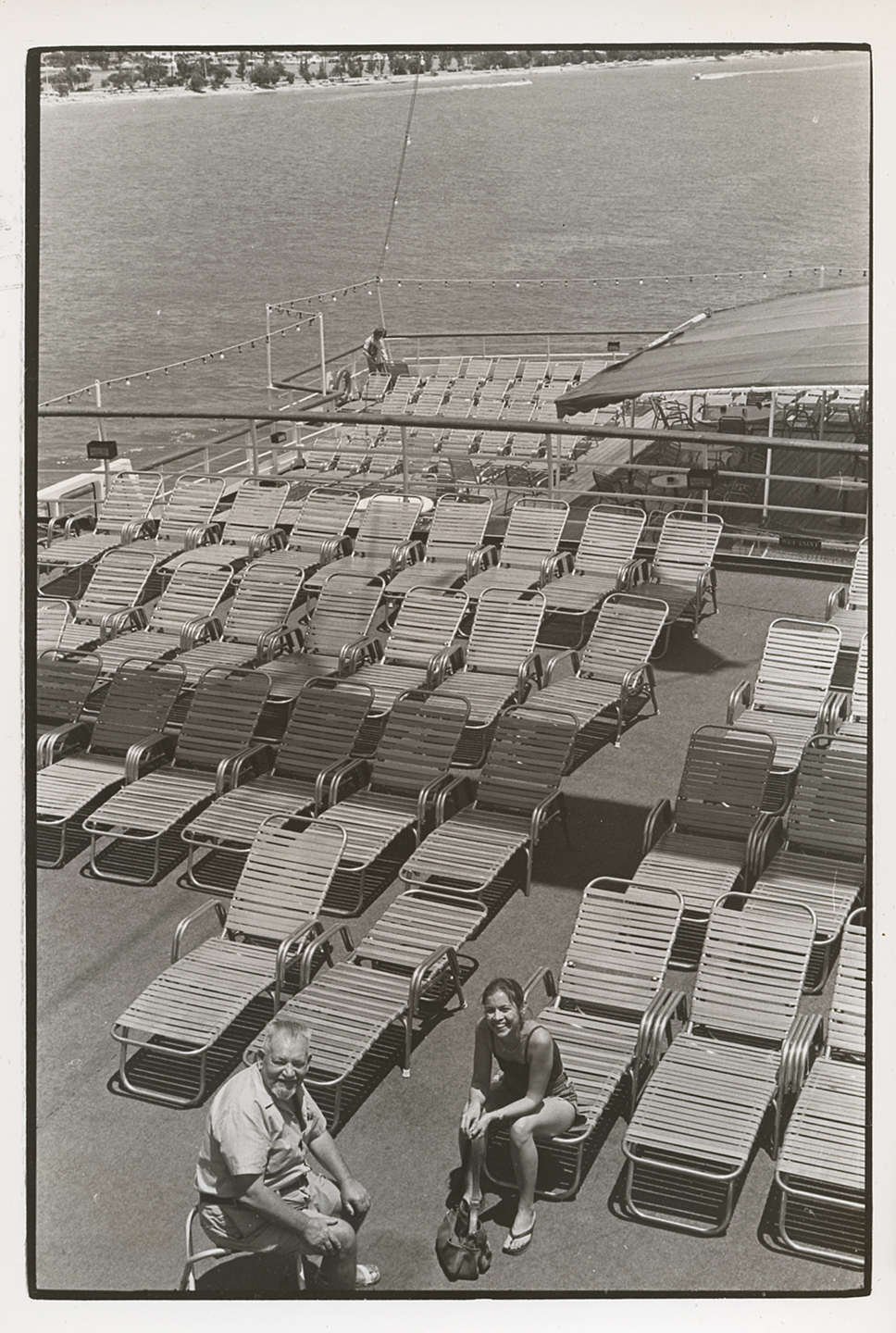

Voronovsky and Teresa Monroe, ca. 1978–1982.

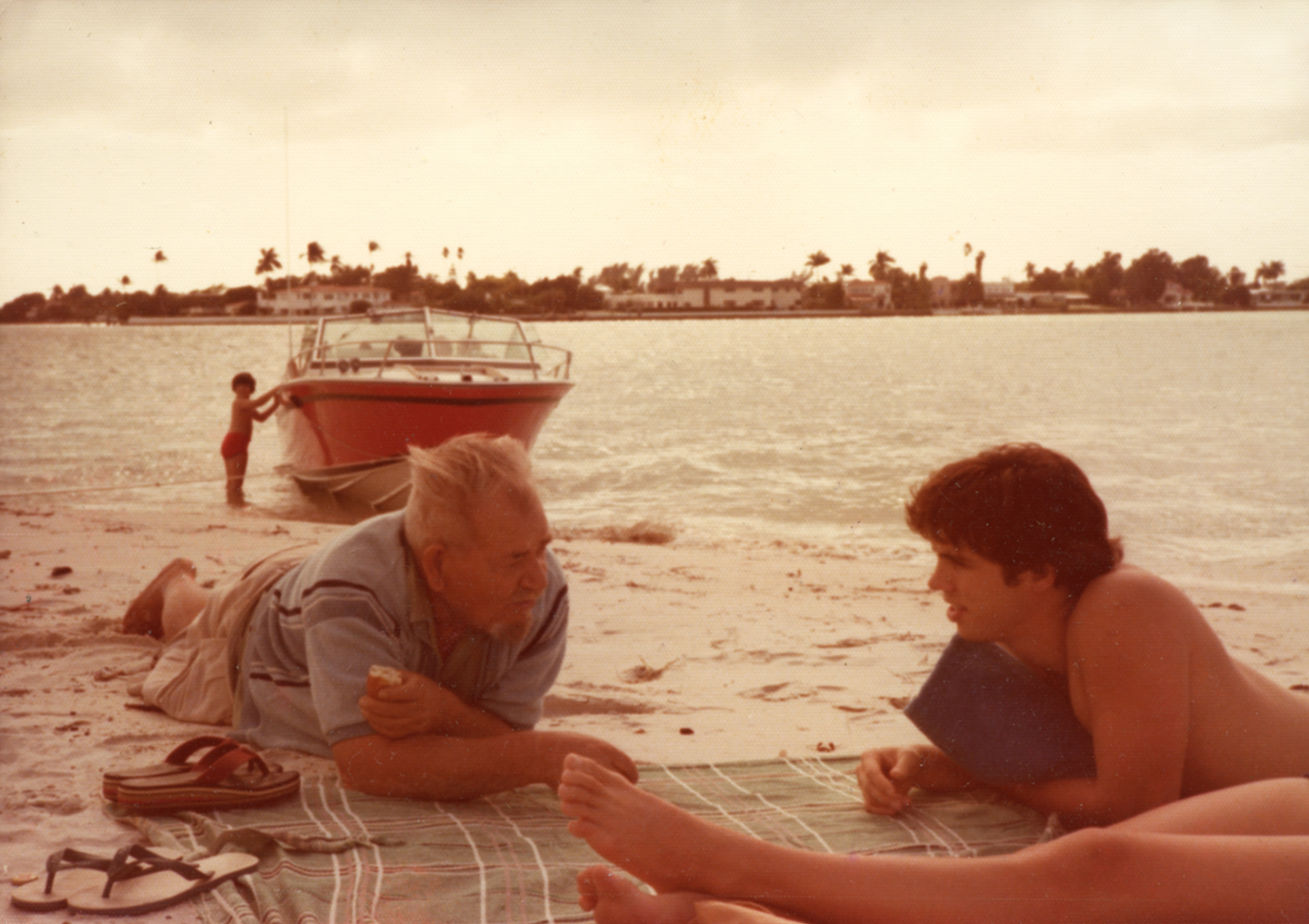

Voronovsky and friends on beach, ca. 1978–1982.

Voronovsky and Michael Gurucharri on beach, ca. 1978–1982.

Voronovsky and friends at Joe’s Stone Crab, ca. 1978–1982.

In 1978, Gary Monroe—a young artist who was photographing Miami and its elder community—was walking along the sidewalk in front of the Colony Hotel and looked up to see decorations that Voronovsky had hung from his window dangling and glinting in the sunlight. Monroe knocked on Voronovsky’s door and began a relationship that would last for the next four years. Monroe and his friends visited Voronovsky frequently, listening to him perform on his accordion, tasting dishes he prepared, and taking him boating and to eat at Miami Beach institutions like Joe’s Stone Crab. With Monroe’s encouragement, Voronovsky applied for and received a grant from the Florida Arts Council that enabled him to purchase canvas and higher-quality paints.

Rebecca Towers, Miami Beach, ca. 1981–1982.

Cruise Ship in Port of Miami, ca. 1981–1982.

Untitled (Cruise Ship), 1972–1982, paint on cardboard, courtesy of the Monroe Family Collection.

His heath failing, Voronovsky had relocated to a senior housing facility not far from the Colony Hotel called Rebecca Towers. Located on the bayside of Miami Beach, Rebecca Towers featured an undisturbed view of the port of Miami and its cruise ship terminals, which Voronovsky captured with his camera and in his art. Before he moved, he wanted to be sure that Rebecca Towers would permit him to recreate his artful interior in his new apartment. He died on July 12 at the age of seventy-eight.

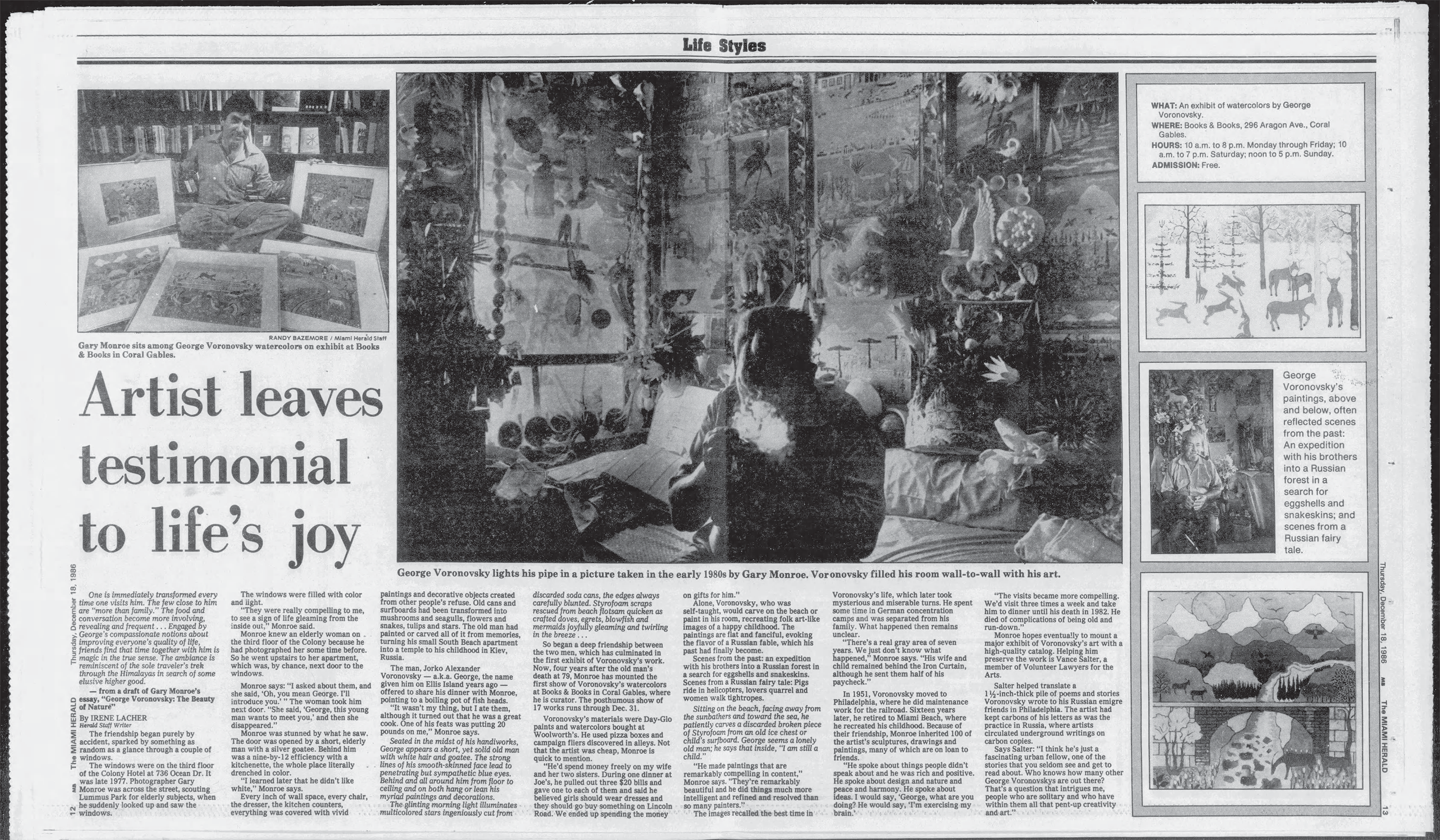

Issue of Miami Herald from December 18, 1986. © 2023 Newspapers.com.

Gary Monroe organized an exhibition in 1986 of Voronovsky’s work at Books & Books, a newly opened bookstore in Coral Gables that has since become a Miami institution. Voronovsky’s work was billed as a “visual celebration of life” and received a two-page spread in the Miami Herald. A year later, his work was part of a group show called A Separate Reality: Florida Eccentrics.

Installation photo of Voronovsky’s work at Boca Raton Museum of Art, 2021.

Voronovsky’s work was not publicly exhibited again until its inclusion in An Irresistible Urge to Create: The Monroe Family Collection of Florida Outsider Art, which opened at the Boca Raton Museum of Art and subsequently traveled to the Tampa Museum of Art and the Mennello Museum of American Art. The High’s 2023 exhibition George Voronovsky: Memoryscapes is the first time the artist’s work has been exhibited outside of Florida and is the first art historical treatment of his paintings and sculptures.