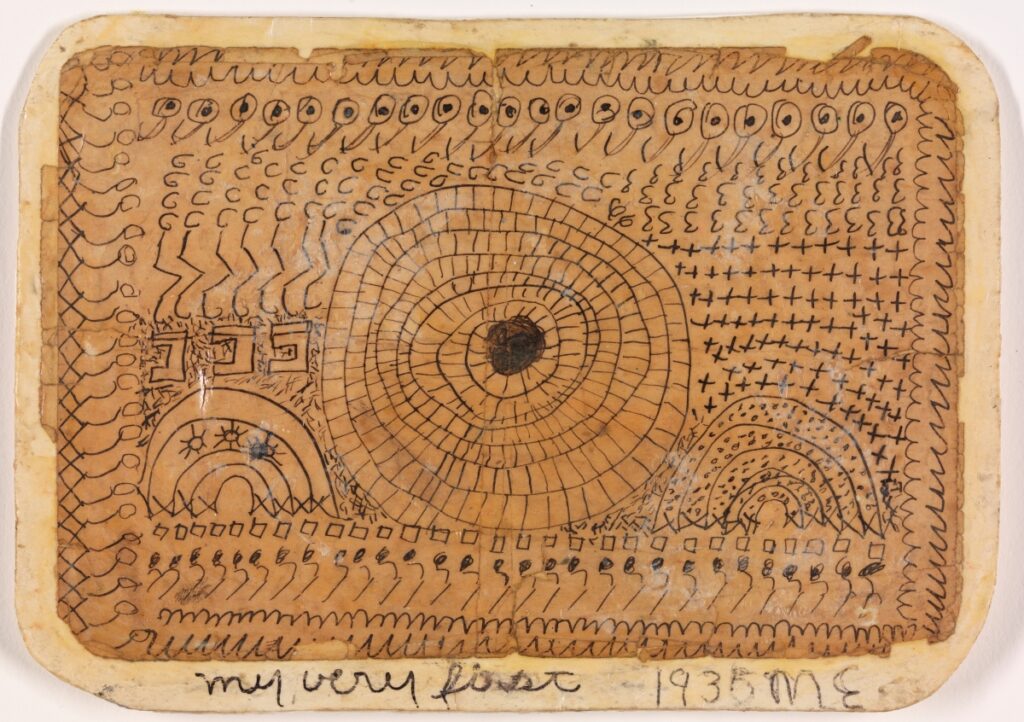

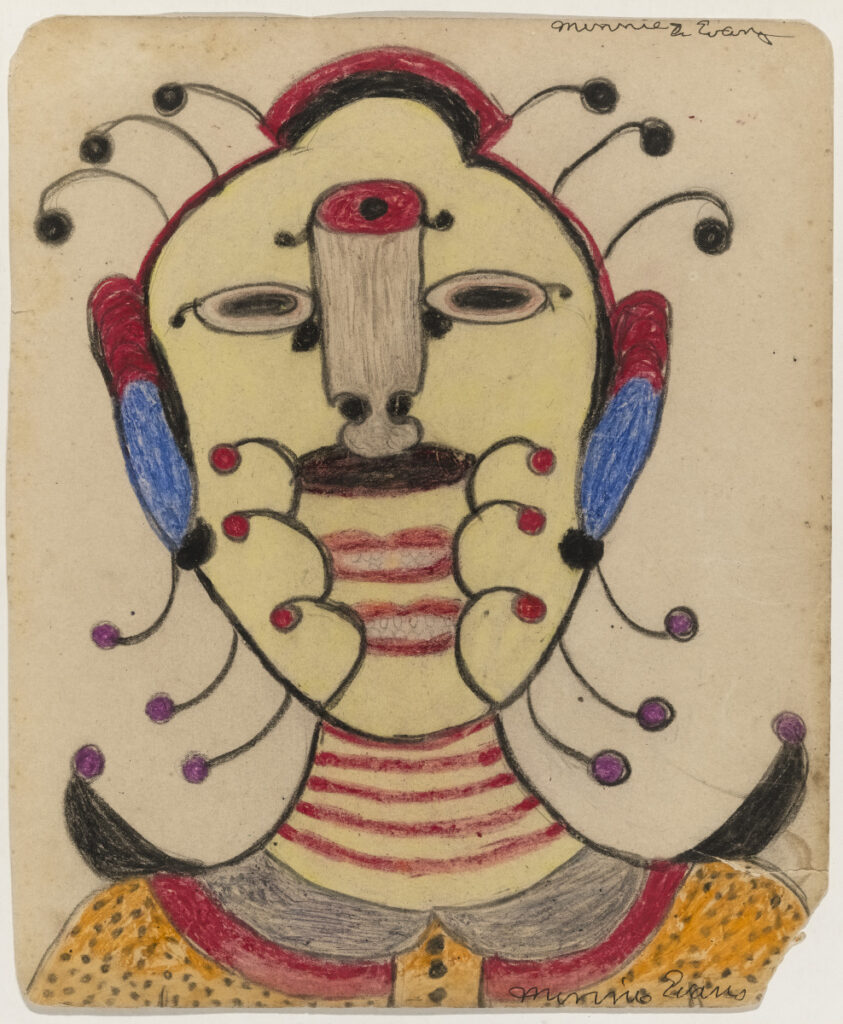

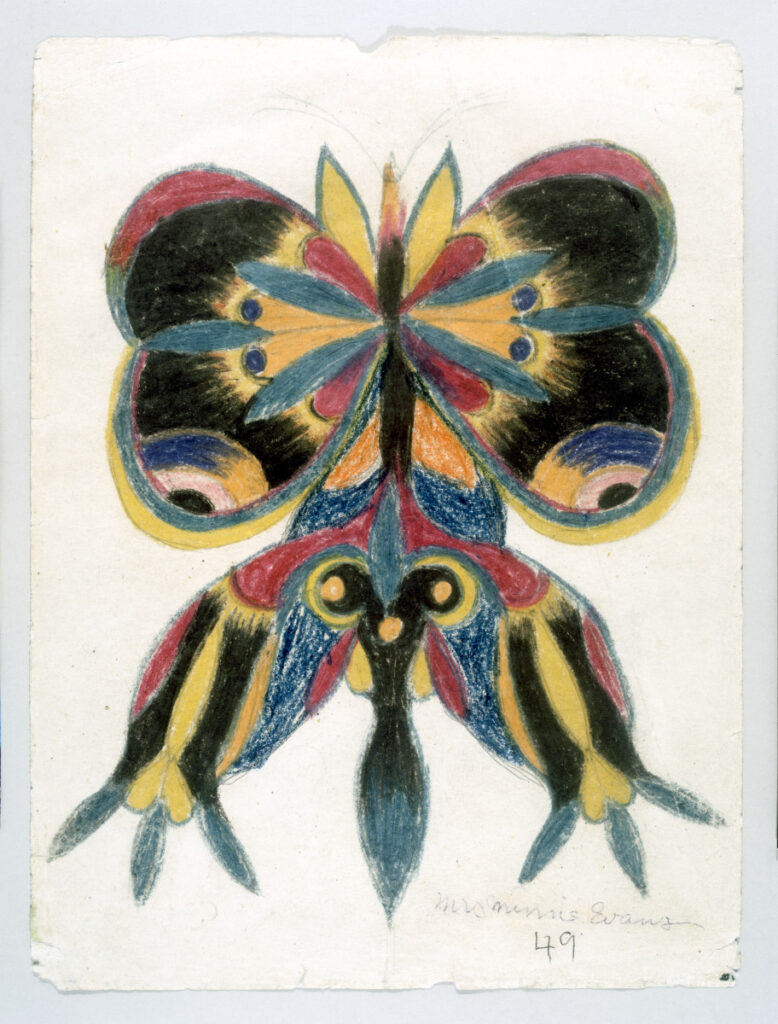

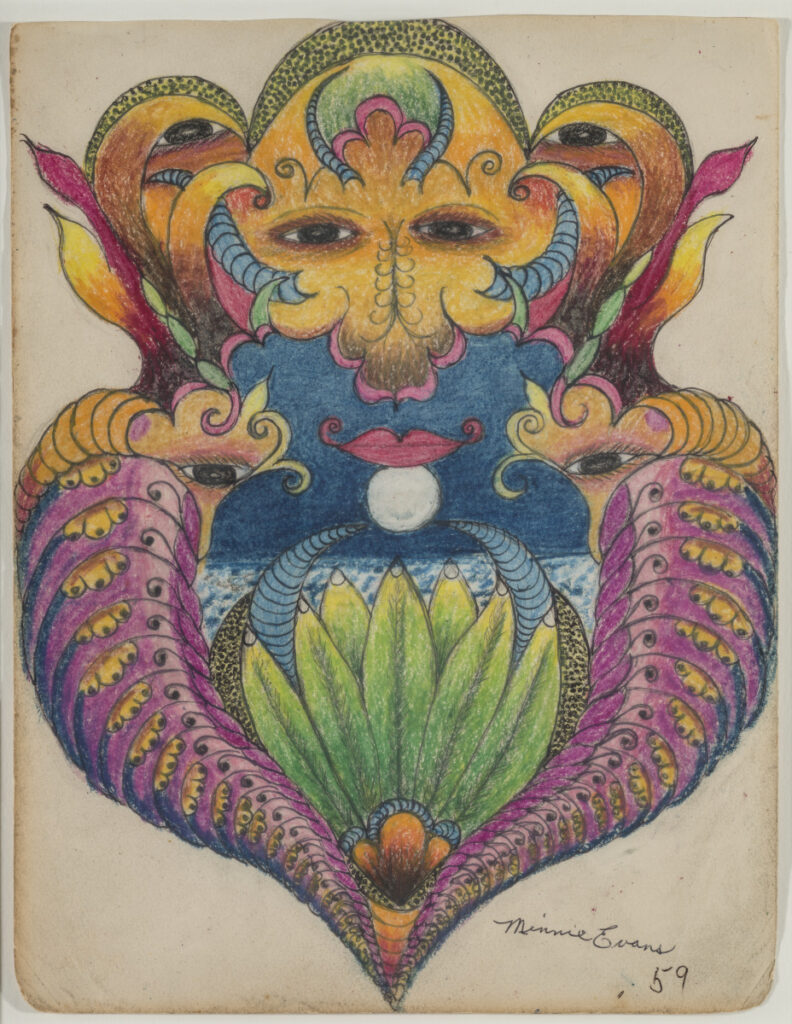

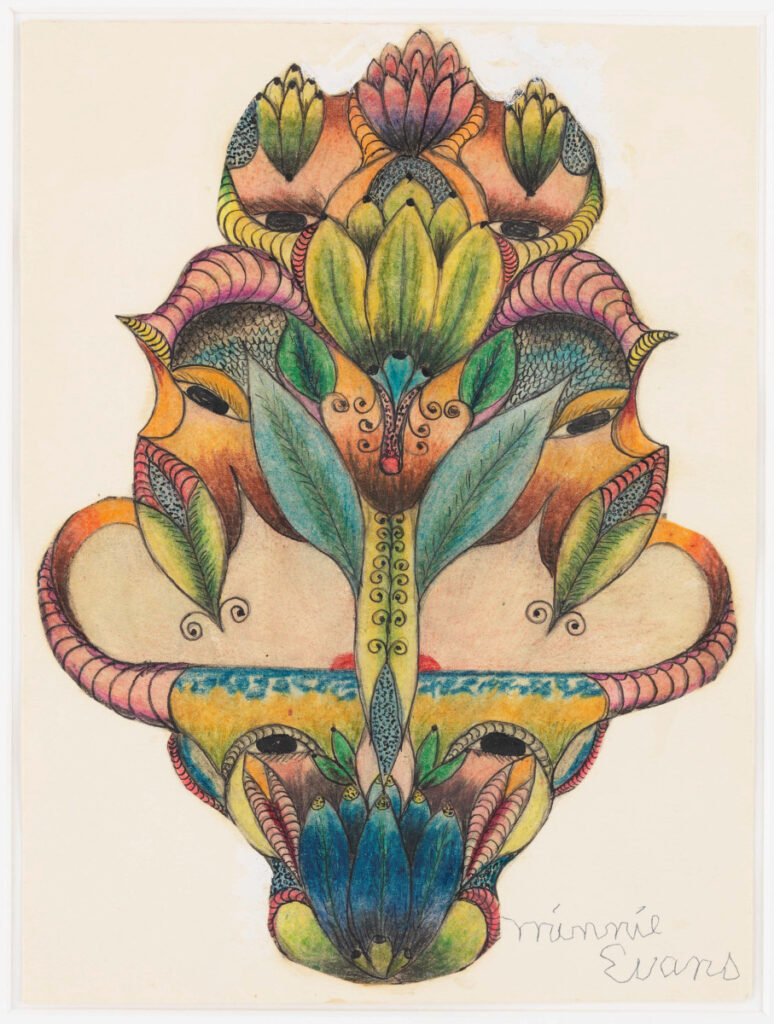

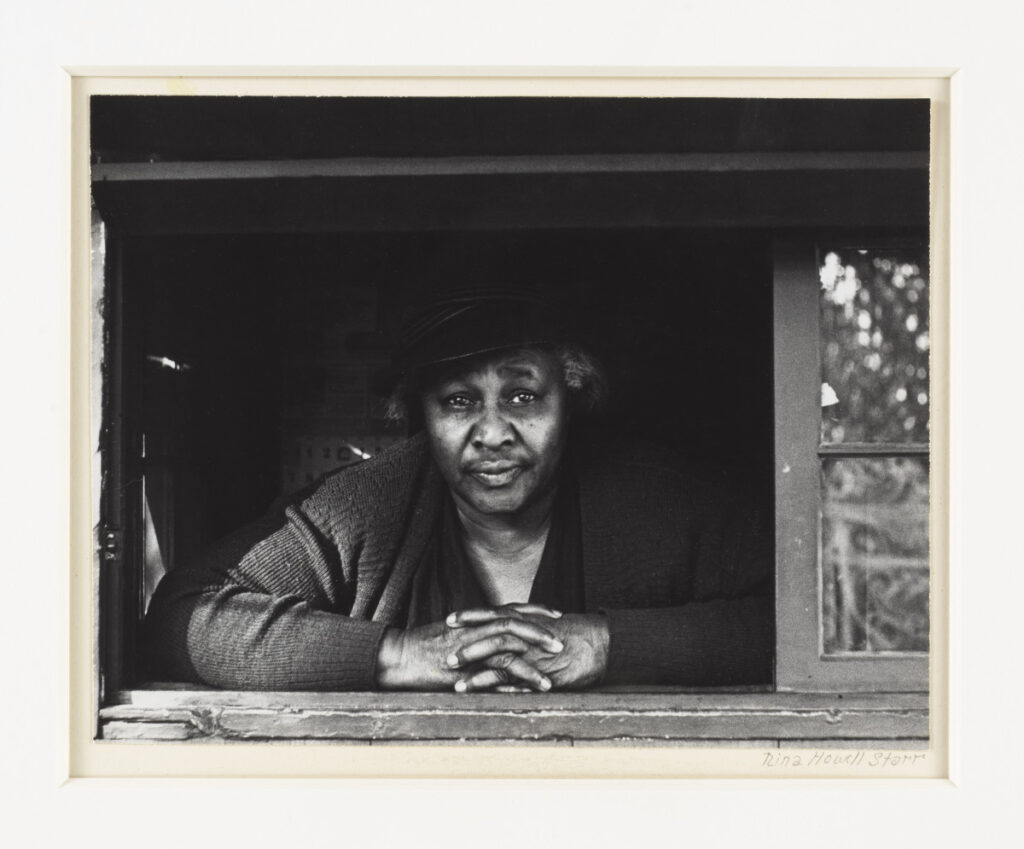

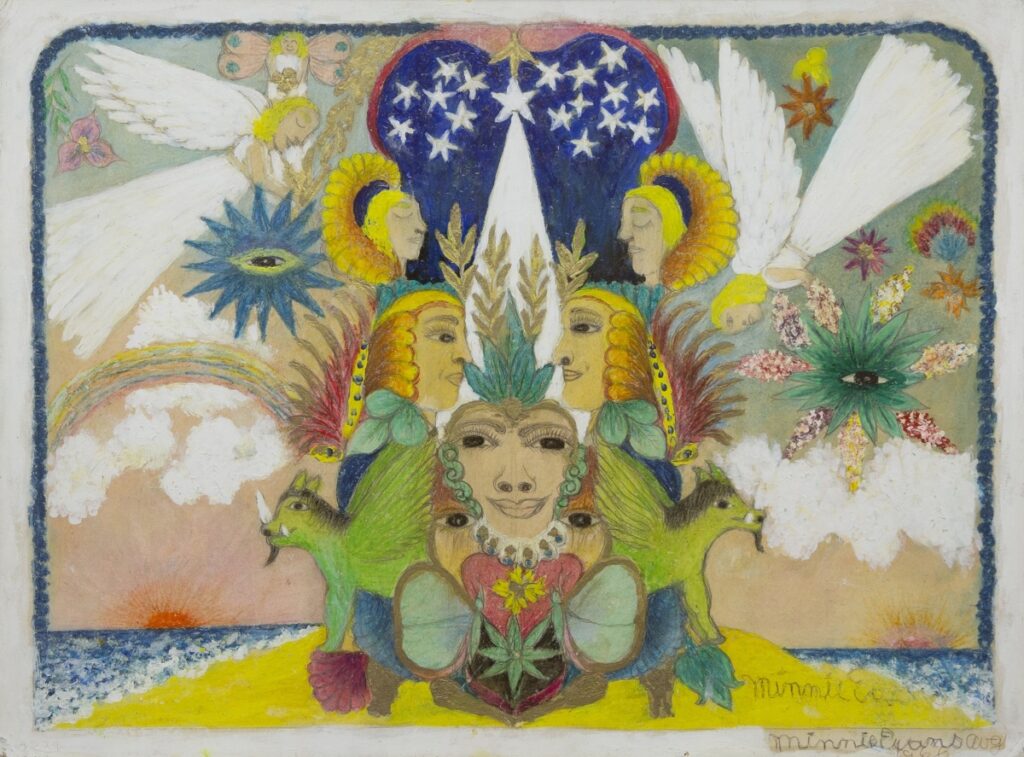

Minnie Evans once said her drawings of harmoniously intertwined human, botanical, and animal forms came from visions of “the lost world,” or nations destroyed by the Great Flood as described in the Book of Genesis. After her grandmother died in 1934 and the visions she experienced in childhood became stronger, Evans produced a large body of work ranging from abstract to representational styles. Though she found fame beyond her community in Wilmington, North Carolina—she was among the first Black artists to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1975—she has not been the subject of a major exhibition since the 1990s.

When Evans turned fifty-six, she shifted from decades of employment as a domestic worker to collecting admissions at Airlie Gardens, one of the most beautifully landscaped gardens in the Southeastern United States. She made art during idle moments and hung it on and near the Gardens’ exquisite wrought-iron gate. Selling or giving away her drawings to Airlie’s visitors led to a reputation beyond Wilmington and eventually a 1966 exhibition at a New York church titled The Lost World of Minnie Evans.

The High’s presentation reprises that 1966 title, honoring Evans’s interest in biblical and ancient civilizations while foregrounding the spiritual and historical circumstances of her extraordinary life. More than one hundred of her artworks are presented in a range of contexts, from the extrasensory experiences of her visions to the double-edged realities of her life in the Jim Crow South. Her drawings, beautiful and complex, thus become portals into her “lost world.”